Uniform Laws - Determination of Death Act/Anatomical Gifts - Future Legislation

Peter Langrock, Esq.

Page 2 of 2

This is the crux of the act. Traditionally and until this time death was described as the stopping of the heart, the stopping of the circulatory system. You've got to think not in terms of 2006 but in terms of 1967 when this Anatomical Death Act was the concern of the Coroners and the medical profession. These people who were trained 30, 40 years earlier, they really did not have a modern concept of what was happening to the body as it died.

This to us today, the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain seems pretty straightforward, but at that time it was not straightforward. So there was a great deal of debate. There is a great deal of debate over the Anatomical Gift Act, the type of debate which echoes some thoughts here would be when you take somebody's heart and, of course, in those days we weren't even talking about heart. We were talking about corneas, and as we moved up, but once you take the heart, which traditionally this, for lack of a better word, the soul of the person, the center there, for generations. The expression, you know, the heart of the matter is, when that is transplanted to another person, what is that person? Who is that person? What is the effect? Is the heart a spare body part or is it the essence and soul of that person? So within the conference the debate went on at all sorts of levels. The lawyers who came from traditional backgrounds were really concerned about what are timately metaphysical problems, not realizing the importance of them, but on the same token coming up with the joint work of the American Bar Association and the American Medical Association.

After the conference passed this by the procedure I said before, it was then approved by the American Medical Association in 1981 or '82. It was approved by the American Bar Association and then it was sent to the states. This today is basically the law throughout the country. If you note, a determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards. That is a question which is still open today, and those standards are changing and being dealt with, but the essence is the cessation of brain function is death.

Image 4: Anatomical Gift

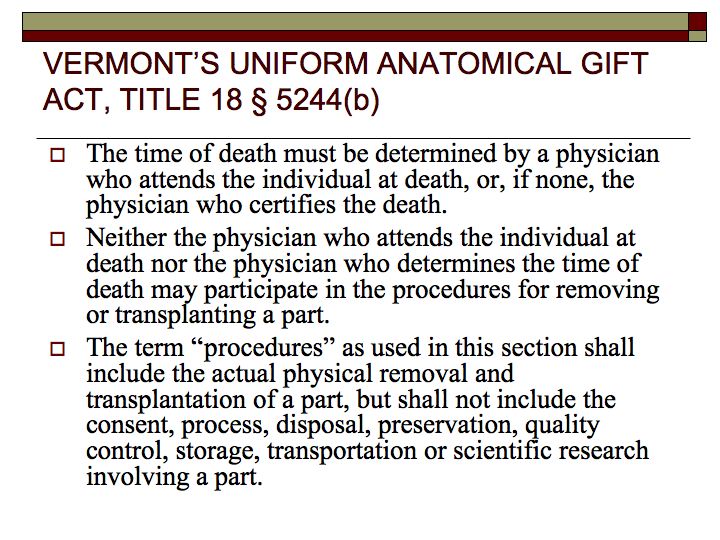

Now, this becomes obviously important – this is Vermont's Uniform Anatomical Gift Act. It's taken from the Uniform Act and I think it's virtually the same in all the states. You'll note the protections here to prevent the premature harvest of organs, and this is one of the fears and one of the problems that the commissioners were concerned with.

Just this past summer we did another revision and each time this comes up there is a more sophisticated scientific background and more interesting debate in some ways. One of the debates is the free market debate and the right to sell organs or the right to will them. There is a major group who feels that they should only be given away: it's a generous gesture and when you die that it should go through a charitable organization and should not be in the free market.

And there are those of us who – I, coming from the Chicago School of Economics -- believe the free market is an appropriate place for most anything. I would put the hypothetical out that if you had a chance to sell your organs upon your death, receive compensation for them by your will, to benefit your children to let them go through college which they could not otherwise do, or some other worthwhile thing, why should that be prohibited? Why should the society impose a moral value against sale of an organ? We see the debate right now and it's just the surface of the debate of being able to sell a kidney. As I understand it you can function on one kidney virtually as well as you can on two kidneys.

The marginal life expectancy is very small. If I have poverty and I have children that I want to send to college and they have an opportunity to do that, and I need the cash, or some other worthwhile thing (I like to use children in college because that's one that really resounds to a lot of us), why should I not be able to do so?

Those are some of the debates. I can say that I was unsuccessful in persuading the Conference that the marketplace should prevail. It may well be there are too many problems and costs, but at least it's the type of debate that is had there. Right now I'm also serving on a committee involving the misuse of genetic information.

As all of you, I'm sure are aware, that the Human Genome Project has just opened up whole new avenues for our society. Prior to that most predictions of individual future health were based upon statistical matters.

Today in some area we can have with a hundred percent certainty, like in Huntington's, if you have the marker, you're going to get it, it's only a matter of time. In breast cancer, there is certain markers which increase dramatically the potential for it. The ethical questions that come out of that, of whether you have a daughter, you should tell her about it. Whether you have a fetus and you have fetus selection based upon gender, all of these matters come into it.

Of course, because these are so interesting, being lawyers, we dealt with two things we could understand, insurance and employment. And so the broad based bill at this point -- or the broad based approach to the conference has not gone forward, but we are in the process of trying to draft legislation to deal with some of the insurance problems and some of the employment problems.

Insurance problems include, if you have a community based rating system like in health insurance, it's not really a problem. If you have insurance that's life insurance, the potential for fraud, the potential for somebody with a high marker going in and buying an insurance policy which is completely out of the underwriting portion, somebody is going to subsidize that.

And the question is should society subsidize a certain amount of insurance, say a hundred thousand for everybody, so you're entitled to that as a sort of community rating? Or do we have a situation where there is a million dollar policy or ten million?

So those problems exist there and we are working right now with the life insurance industry, the toughest one to deal with in this area. In the employment area there is a basic feeling of privacy that people's genetic information should not be generally available.

| If you asked the populous as a whole, if this person has a predisposition to pedophilia should he or she be allowed to teach in a grade school? | A hypothetical that's used, it's not here yet but it may be, if we find a marker for predisposition to pedophilia, what is the effect of that in a social system? |

The civil rights, the gut reaction is, it's nobody's business until somebody does something, we shouldn't consider it. If you asked the populous as a whole, if this person has a predisposition to pedophilia should he or she be allowed to teach in a grade school? We have the same type of thing with the predisposition to blackouts for airline pilots. We have all sorts of other employment, potentially to regulate problems that come from genetic markers.

The problem is every time I go to a meeting the whole science has changed. We are developing information on markers at some ridiculous rate, unbelievable rate of 50 a week or, maybe it's ten a week, but it's outstripping. So lawyers, again, are going to be playing catch up. What we are doing in this act, we are playing catch up. In the Determination of Death and in the genetic field, I've been talking to the Scope and Program for eight or ten years about trying to get a genetic project. I say the genetic revolution is going to be as important to our society from a social standpoint, from a political standpoint, as the information revolution, as the industrial revolution. It has potential to really effect us in ways we should be thinking about and trying to get ahead, and we are getting ahead of. We are taking employment and insurance, we are playing catch up.

So what I see and the future is that the law is going to have to play catch up to fascinating concepts that we are talking about here today. I just have found this morning all the presentations just absolutely mind expanding and wonderful. I'm trying to think about how I can make a presentation to the conference to get them thinking about what type of regulatory bodies that we have, and might be needed.

You know, when we discovered electricity, we didn't have a public utilities regulation system. You know, once we start bringing this into the public there is always a motion or a movement to try to regulate it.

And, stem cell research, we have the prohibitions. One of the things which I believe passionately, and that is to just say "no" doesn't work. To say no to advance, I don't care what it is, whether it be stem cell research, human cloning, whatever your moral values, you may not like it, but prohibition has never accomplished anything. All it does is move things around. I mean stem cell research, what we are seeing is the economic potential will no longer be in the United States, it will be in the Cayman Islands or someplace else; it's not going to stop. And so, again, we are going to see the law trying to catch up mainly in a regulatory system, because right now the law is trying to prevent it.

I was once involved in the Uniform Privacy Act which never really got off. And Nick Katzenbach and I were talking, he was then president of IBM, and he said, "Peter, you can't prevent the assimilation. Maybe you can have some sort of control over the dispensing of the information." And I think that's so true, and so what if we do it on a regulatory basis? So that while I'm just fascinated by some of the finest minds thinking about all of the artificial intelligence, these things out here, I am saying we are going to have to deal with this on a very plebian basis in the state legislatures across the country to not block science, but to encourage it and to do so in a fashion which is consistent with the overall morals of our society.

And I see the role of the Conference of Commissioners, again going back to 1982 and hitting Thousands of topics, having lots and lots of meetings in the future, and I wish, I hear this, I wish I was 40 again. You know, it's just so much excitement out here. Maybe we will figure ways I can live that long. I look forward to helping participate in the types of law development, that will forward the goals of morality, as I see it, mine is the right one like everybody believes there is and the controls that will be necessary to prevent some of the problems but without stifling.

Human Genome Project - Completed in 2003, the Human Genome Project (HGP) was a 13-year project coordinated by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health. During the early years of the HGP, the Wellcome Trust (U.K.) became a major partner; additional contributions came from Japan, France, Germany, China, and others. See our history page for more information. http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/home.shtml April 13, 2007 4:47PM EST

Nicholas DeBelleville Katzenbach (born January 17, 1922) is an American lawyer who served as United States Attorney General during the Lyndon B. Johnson administration.

http://www.zoominfo.com/Search/PersonDetail.aspx?PersonID=3843318 April 13, 2007 5:01PM EST

BIO

Peter F. Langrock, Esq.

Peter F. Langrock, Esq.

Peter has been a practicing trial attorney since 1960, with articles appearing in such publications as: The American Bar Association Journal, Trial Magazine, and many other periodicals. Peter served on the committee associated with the Uniform Determination of Death Act from 1967 to 1981 and presently serves on the Committee on Misuse of Genetic Information in Insurance and Employment.