Constitutional Personhood

Michael Rivard, Esq.

Page 4 of 4

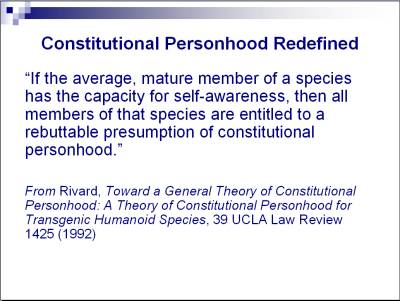

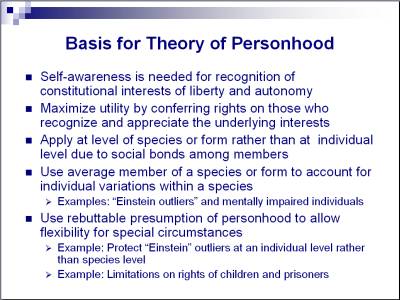

You maximize overall utility, so we are getting away from the natural rights argument and into modern utilitarian moral theory, by conferring autonomy and liberty rights on those who recognize them. In the example I use in the article, a rich woman loves her dog, so she hires the best tutors, starts teaching the dog how to read, works at it for a couple of years, and in the end the dog simply cannot read. Even though it has had every opportunity to read, it is simply not something that is appreciated or recognized by the dog's consciousness. She would have been better off giving the dog doggy treats that it recognizes and appreciates.

The concept applies to the constitutional interests of liberty and autonomy. You ask whether the average member of a species recognizes and appreciates the constitutional interests of liberty and autonomy. You apply the test at the species  level rather than at an individual level. The protection extends to individuals within the species, even if they themselves cannot recognize constitutional interests, due to social bonds among the members of the species. In other words, it is not about the individual ability to perceive constitutional interests. If it was all about the individual, then those who have mental impairment, those who are in a vegetative state, those who are not self-aware as we think of self-awareness, would not have constitutional rights because it would not enhance utility to grant those rights to those who cannot perceive them.

level rather than at an individual level. The protection extends to individuals within the species, even if they themselves cannot recognize constitutional interests, due to social bonds among the members of the species. In other words, it is not about the individual ability to perceive constitutional interests. If it was all about the individual, then those who have mental impairment, those who are in a vegetative state, those who are not self-aware as we think of self-awareness, would not have constitutional rights because it would not enhance utility to grant those rights to those who cannot perceive them.

Rather than focusing on the perception of the individual, you focus on social interests, the fact that people care about each other, the sort of species cohesion that we have. Thus, an individual who cannot perceive constitutional interests may nevertheless have constitutional rights that, in effect, are derived from other members of the species who do perceive the constitutional interests of liberty and autonomy.

Conversely, using an average member of the species to set a presumption of constitutional personhood for the species still accounts for individual variations that may merit constitutional personhood for that individual. For example, in a species that fails to meet the test or a machine consciousness that fails to meet the test, you may still grant constitutional rights to individuals that meet the test, but not to the species as a whole.

There can be these Einstein outliers who happen to be so far above all of the others of their species that it would be morally incorrect not to give them these constitutional rights.

On the other hand, as I was just saying, mentally impaired individuals, human mentally impaired individuals who may lack self-awareness should not lose their due process rights, for example. Therefore, you can use this rebut-able presumption of personhood to allow flexibility for individual circumstances.

To conclude, a constitutional person is someone or something that is self-aware. If the average member of that group is self-aware, then you just assume from the outset that all members of that group are constitutional persons. However, there is flexibility to treat individuals differently within that group, by rebutting the presumption of full constitutional rights, as already exists today for humans.

The existing law on constitutional personhood is very fragmentary and lacks underlying principles. You cannot extrapolate from what the law is today to where the law would go in the future by the usual analogy and distinction methods that our common law system uses. It is too different. There is nothing to base it on.

In this article, I propose a new approach to constitutional personhood to stimulate discussion, and I believe that this approach may be useful for resolving current issues as well like the constitutional personhood of the fetus.

For example, at the moment, in Roe v. Wade [1] in dictum, a fetus is not considered to be a constitutional person, so a fetus is genetically human but not considered to be a constitutional person. The Court concluded that there is nothing in the Constitution that addresses individuals of this status. A fetus is not counted for a census, for example, so they are not constitutional persons.

This argument seems a bit thin to me. I am not making any conclusions about whether or not the fetus should be a constitutional person, but I believe that the framework provided by the personhood presumption theory can provide us with a way to think about whether or not a fetus is a constitutional person. The question depends not on the intrinsic self-awareness of the fetus but more on the societal bonds that people may have toward the fetus; in particular, the mother and the father. The social bonds give an interest to the parents on behalf of the fetus rather than something being intrinsic to the fetus.

That is one example of how the theory could be used. My suggestion is that we start putting some of this into practice today as these kinds of cases arise to prepare the way for dealing with the issue of constitutional personhood later, so we can begin to close the gap between the current law and what we will need to cover the constitutional personhood of human-animal combinations and other forms of consciousness that may arise in the future. We will have made some progress in the interim.

Footnote

1. Roe V. Wade – 410 U.S.113 (1973) A pregnant single woman (Roe) brought a class action challenging the constitutionality of the Texas criminal abortion laws, which proscribe procuring or attempting an abortion except on medical advice for the purpose of saving the mother's life… Ruling that declaratory, though not injunctive, relief was warranted, the court declared the abortion statutes void as vague and over-broadly infringing those plaintiffs' Ninth and Fourteenth Amendment rights. The court ruled the Does' complaint not justiciable. Appellants directly appealed to this Court on the injunctive rulings, and appellee cross- appealed from the District Court's grant of declaratory relief to Roe and Hallford.

http://members.aol.com/abtrbng/410us113.htm October 17, 2007 1:37PM EST

About the Author

Michael Rivard, Esq. is a Business Developer and Legal Advisor living and working in Natick, Massachusetts. Mr. Rivard first researched and wrote on the topic of Constitutional Personhood for Transgenic Humanoid Species as a student for the UCLA Law Review in 1991.

Michael Rivard, Esq. is a Business Developer and Legal Advisor living and working in Natick, Massachusetts. Mr. Rivard first researched and wrote on the topic of Constitutional Personhood for Transgenic Humanoid Species as a student for the UCLA Law Review in 1991.