An Outline for the Legal Ontology of Personhood:

The Transbeman Example

David Koepsell, Ph.D.

Page 2 of 3

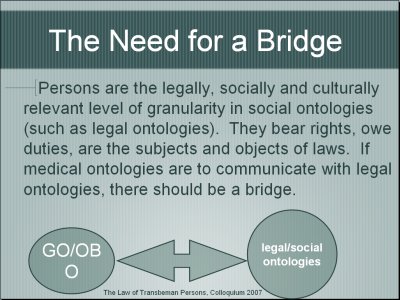

In ontology, a person would include the human portion of the gene ontology as whatever other necessary and sufficient conditions of person hood exist, it would also account for non-biological forms of personhood, of course, some more candidates. I am not pretending to give you the ontology of personhood. When I say things like bearing rights and intentionality and sentience, these are candidates; this is the reason the project is undertaking. This would be tremendously helpful if some of you are involved in IRB [1] work or on ethics committees. I think it would be tremendously helpful and possible based upon the large backlog of data we've accumulated in all of these bioethical undertakings like IRBs and bioethics committees, as well as in case law, to mine that data. This is what we do in ontology in terms of relations to determine whether they track reality in any useful way.

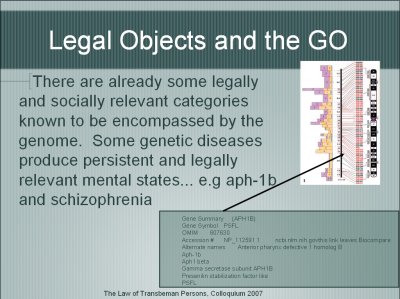

There are already some legally and socially related categories known to be encompassed by the genome and this is one of those examples. For instance, there are some genetic disorders and diseases that are proven to exist and to be  related to legally relevant mental states. Because someone may have Down syndrome or Schizophrenia, they are treated differently by the law and society as they may be persons but they lack certain rights. That is an important first step in developing this ontology of personhood. Which again, is to say that this personhood is not dependent upon the genome but it's certainly informed by it.

related to legally relevant mental states. Because someone may have Down syndrome or Schizophrenia, they are treated differently by the law and society as they may be persons but they lack certain rights. That is an important first step in developing this ontology of personhood. Which again, is to say that this personhood is not dependent upon the genome but it's certainly informed by it.

Certain cognitive and mental states and phenotypes including genetic defects affecting rights such as genetic disabilities covered under the ADA, and even ethnic and racial distinctions recognized by society, culture, and the law relate to the genome already. Again, there is no bridge between these right now but this crude ontology of personhood already exists out there in our culture and in the law. Biomedical, legal, and social ontologies should communicate.

One of the goals of ontological research is developing not just isolated artificial agents, which are being used in diagnostics, but in being able to tie together vocabularies in different realms. Shouldn't bioethicists, doctors, and the legal system communicate through the use of a well-defined, robust vocabulary in which concepts are shared and communicated well?

Image 4

In fact, all social ontologies already assume the existence of a person as distinct from the organism. As I've mentioned, this already exists, it's out there, it's not that we have to start from scratch. Ethical issues such as abortion and stemcell research all depend on distinctions between humans and persons. Blastocysts, fetuses, rights bearing persons, and a fresh human corpse are all legally and social distinct entities, even while they might be biomechanically, in certain cases, identical or similar. For instance, those in persistent vegetative states are neurologically distinct and that's a relevant category. At some point, personhood comes out, just as it comes in under the law.

Image 5

Footnote

1. IRB/IEC (Institutional Review Board or Independent Ethics Committee – also known as an Ethical Review Board) - a group that has been formally designated to approve, monitor, and review biomedical and behavioral research involving humans with the alleged aim to protect the rights and welfare of the subjects. In the United States, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and HHS regulations have empowered IRBs to approve, require modifications in (to secure approval), or disapprove research. An IRB performs critical oversight functions for research conducted on human subjects that are scientific, ethical, and regulatory.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institutional_Review_Board January 24, 2008 2:43PM EST

1 2 3 next page>