Constitutional Personhood

Michael Rivard, Esq.

Page 2 of 4

It is a lot messier when you look at to the constitutional personhood of juridical persons. A number of different legal theories have evolved over the years. The original legal theory was that corporations are artificial entities. They are a creation of the State; therefore, they have no rights.

That theory quickly gave way as corporations became larger, as with railroads and things like that in the 1800s. Judges began looking at the corporation as an aggregate of natural persons. The shareholders needed protection.

Then as companies became larger, the theory evolved that rights of corporations are not necessarily derived solely from their shareholders, but that the corporation itself is more of a separate entity for purposes of constitutional personhood. Because management may go against the interest of shareholders, at least for a period, the corporation has its own "will" that is determined by management.

More recently, we have seen that the application of constitutional rights to entities depends of the nature of the constitutional right rather than the nature of the organization. Judges look at the history of the constitutional right, what it is designed to do, and then decide whether to grant that right to the corporation.

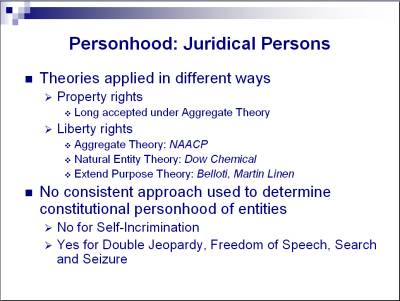

These theories of constitutional personhood are applied in different ways. For property rights, it has long been accepted that corporations are constitutional persons under the aggregate theory. This makes sense, right? Corporations and partnerships are composed of individual investors who have property rights in the corporation. Thus, the corporation is granted constitutional property rights as a collection of individuals.

On the other hand, constitutional liberty rights for corporations have steadily been evolving. You see cases like NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), in which NAACP has standing to litigate under the aggregate theory. NAACP is an aggregate of individuals who have come together for political speech. Therefore, NAACP is a constitutional person.

Then we see the natural entity theory, which is shown in Dow Chemical, where the Court uses words like, "Dow would have a reasonable expectation of privacy," as if Dow is a human being.

Finally, we see the Court turn to the theory of extending constitutional rights based on the history of the right rather than the status of the entity. This is illustrated in Belloti and Martin Linen.[1] These two cases are often combined in arguments. What comes out of this line of cases and legal theories is that there is no consistent approach used to determine the constitutional personhood of entities. A corporation is not a constitutional person for purposes of the right against self-incrimination, at least when I wrote this, but is a person for purposes of double jeopardy, freedom of speech and search and seizure.

Interestingly, the self-incrimination case was a corporation or partnership with three individuals, so one would expect the aggregate theory to apply. We see very inconsistent results.Footnote

1. Bellotti - U.S. Supreme Court FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF BOSTON v. BELLOTTI, 435 U.S. 765 (1978) 435 U.S. 765

Appellants, national banking associations and business corporations, wanted to spend money to publicize their views opposing a referendum proposal to amend the Massachusetts Constitution to authorize the legislature to enact a graduated personal income tax. They brought this action challenging the constitutionality of a Massachusetts criminal statute that prohibited them and other specified business corporations from making contributions or expenditures "for the purpose of . . . influencing or affecting the vote on any question submitted to the voters, other than one materially affecting any of the property, business or assets of the corporation." The statute specified that "[n]o question submitted to the voters solely concerning the taxation of the income, property or transactions of individuals shall be deemed materially to affect the property, business or assets of the corporation." On April 26, 1976, the case was submitted to a single Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts on an expedited basis and upon agreed facts. Judgment was reserved and the case was referred to the full court. On September 22, 1976, the court directed entry of a judgment for appellee and issued its opinion upholding the constitutionality of the statute after the referendum, at which the proposal was rejected.

http://supreme.justia.com/us/435/765/case.html October 17, 2007 1:19PM EST

Martin Linen – U.S. Supreme Court UNITED STATES v. MARTIN LINEN SUPPLY CO., 430 U.S. 564 (1977) 430 U.S. 564

After a deadlocked jury was discharged when unable to agree upon a verdict at the criminal contempt trial of respondent corporations, the District Judge granted respondents' timely motions for judgments of acquittal under Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 29 (c), which provides that "a motion for judgment of acquittal may be made . . . within 7 days after the jury is discharged [and] the court may enter judgment of acquittal. . . ." The Government appealed pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 3731, which allows an appeal by the United States in a criminal case "to a court of appeals from a . . . judgment . . . of a district court dismissing an indictment . . ., except that no appeal shall lie where the double jeopardy clause of the United States Constitution prohibits further prosecution." The Court of Appeals dismissed the appeal. Held: The Double Jeopardy Clause bars appellate review and retrial following a judgment of acquittal entered under Rule 29 (c). Pp. 568-576. http://supreme.justia.com/us/430/564/case.html October 17, 2007 1:20PM EST

1 2 3 4 next page>